Leadership and Organizational Behavior

Organizational Behavior (OB) is the study and application of knowledge about how people, individuals, and groups act in organizations. It does this by taking a system approach. That is, it interprets people-organization relationships in terms of the whole person, whole group, whole organization, and whole social system. Its purpose is to build better relationships by achieving human objectives, organizational objectives, and social objectives.

As you can see from the definition above, organizational behavior encompasses a wide range of topics, such as human behavior, change, leadership, teams, etc. Since many of these topics are covered elsewhere in the leadership guide, this paper will focus on a few parts of OB: elements, models, social systems, OD, work life, action learning, and change.

Elements of Organizational Behavior

The organization's base rests on management's philosophy, values, vision and goals. This in turn, drives the organizational culture that is composed of the formal organization, informal organization, and the social environment. The culture determines the type of leadership, communication, and group dynamics within the organization. The workers perceive this as the quality of work life which directs their degree of motivation. The final outcome are performance, individual satisfaction, and personal growth and development. All these elements combine to build the model or framework that the organization operates from.

Models of Organizational Behavior

There are four major models or frameworks that organizations operate out of, Autocratic, Custodial, Supportive, and Collegial (Cunningham, Eberle, 1990; Davis ,1967):

- Autocratic — The basis of this model is power with a managerial orientation of authority. The employees in turn are oriented towards obedience and dependence on the boss. The employee need that is met is subsistence. The performance result is minimal.

- Custodial — The basis of this model is economic resources with a managerial orientation of money. The employees in turn, are oriented towards security, benefits, and dependence on the organization. The employee need that is met is security. The performance result is passive cooperation.

- Supportive — The basis of this model is leadership with a managerial orientation of support. The employees in turn are oriented towards job performance and participation. The employee need that is met is status and recognition. The performance result is awakened drives.

- Collegial — The basis of this model is partnership with a managerial orientation of teamwork. The employees in turn are oriented towards responsible behavior and self-discipline. The employee need that is met is self-actualization. The performance result is moderate enthusiasm.

Although there are four separate models, almost no organization operates exclusively in one. There will usually be a predominate one, with one or more areas over-lapping with the other models.

The first model, autocratic, has its roots in the industrial revolution. The managers of this type of organization operate mostly out of McGregor's Theory X. The next three models build on McGregor's Theory Y. They have each evolved over a period of time and there is no one best model. In addition, the collegial model should not be thought as the last or best model, but the beginning of a new model or paradigm.

Social Systems, Culture, and Individualization

A social system is a complex set of human relationships interacting in many ways. Within an organization, the social system includes all the people in it and their relationships to each other and to the outside world. The behavior of one member can have an impact, either directly or indirectly, on the behavior of others. Also, the social system does not have boundaries ... it exchanges goods, ideas, culture, etc. with the environment around it.

Culture is the conventional behavior of a society that encompasses beliefs, customs, knowledge, and practices. It influences human behavior, even though it seldom enters into their conscious thought. People depend on culture as it gives them stability, security, understanding, and the ability to respond to a given situation. This is why people often fear change. They fear the system will become unstable, their security will be lost, they will not understand the new process, and they will not know how to respond to the new situations.

Individualization is when employees successfully exert influence on the social system by challenging the culture.

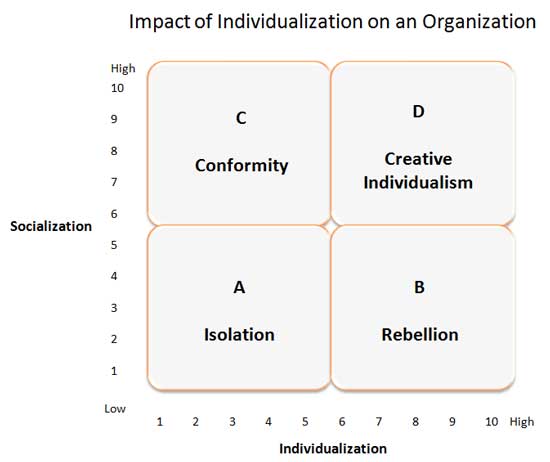

The quadrant below shows how individualization affects different organizations (Schein, 1968):

- Quadrant A — Too little socialization and too little individualization creates isolation.

- Quadrant B — Too little socialization and too high individualization creates rebellion.

- Quadrant C — Too high socialization and too little individualization creates conformity.

- Quadrant D — The match that organizations want to create is high socialization and high individualization for a creative environment. This is what it takes to survive in a very competitive environment ... having people grow with the organization, but doing the right thing when others want to follow the easy path.

This can become quite a balancing act. Individualism favors individual rights, loosely knit social networks, self-respect, and personal rewards and careers—it may become look out for Number One! Socialization or collectivism favors the group, harmony, and asks, “What is best for the organization?” Organizations need people to challenge, question, and experiment, while still maintaining the culture that binds them into a social system.

Organization Development

Organization Development (OD) is the systematic application of behavioral science knowledge at various levels, such as group, inter-group, organization, etc., to bring about planned change (Newstrom, Davis, 1993). Its objectives are a higher quality of work-life, productivity, adaptability, and effectiveness. It accomplishes this by changing attitudes, behaviors, values, strategies, procedures, and structures so that the organization can adapt to competitive actions, technological advances, and the fast pace of change within the environment.

There are seven characteristics of OD (Newstrom, Davis, 1993):

- Humanistic Values: Positive beliefs about the potential of employees (McGregor's Theory Y).

- Systems Orientation: All parts of the organization, to include structure, technology, and people, must work together.

- Experiential Learning: The learners' experiences in the training environment should be the kind of human problems they encounter at work. The training should NOT be all theory and lecture, but rather provide experiences that create learning opportunities.

- Problem Solving: Problems are identified, data is gathered, corrective action is taken, progress is assessed, and adjustments in the problem solving process are made as needed. This process is known as Action Research.

- Contingency Orientation: Actions are selected and adapted to fit the need.

- Change Agent: Stimulate, facilitate, and coordinate change.

- Levels of Interventions: Problems can occur at one or more level in the organization so the strategy will require one or more interventions.

Quality of Work Life

Quality of Work Life (QWL) is the favorableness or unfavorableness of the job environment (Newstrom, Davis, 1993). Its purpose is to develop jobs and working conditions that are excellent for both the employees and the organization. One of the ways of accomplishing QWL is through job design. Some of the options available for improving job design are:

- Leave the job as is but employ only people who like the rigid environment or routine work. Some people do enjoy the security and task support of these kinds of jobs.

- Leave the job as is, but pay the employees more.

- Mechanize and automate the routine jobs.

- And the area that OD loves—redesign the job.

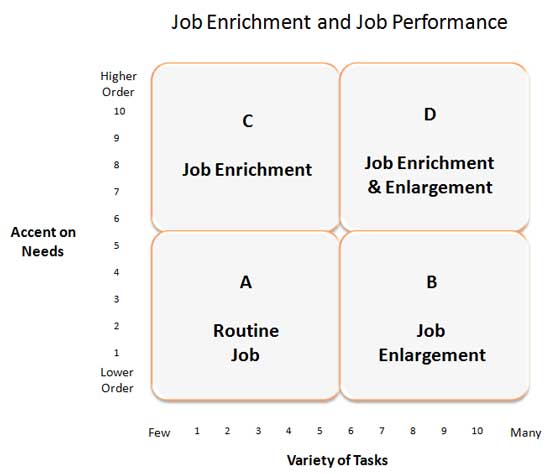

When redesigning jobs there are two spectrums to follow—job enlargement and job enrichment. Job enlargement adds a more variety of tasks and duties to the job so that it is not as monotonous. This takes in the breadth of the job. That is, increase the number of different tasks that an employee performs. This can also be accomplished by job rotation.

Job enrichment, on the other hand, adds additional motivators. It adds depth to the job—more control, responsibility, and discretion to how the job is performed. This gives higher order needs to the employee, as opposed to job enlargement that simply gives more variety. The chart below illustrates the differences (Cunningham, Eberle, 1990):

The benefits of enriching jobs include:

- Growth of the individual

- Individuals have better job satisfaction

- Self-actualization of the individual

- Better employee performance for the organization

- Organization gets intrinsically motivated employees

- Less absenteeism, turnover, and grievances for the organization

- Full use of human resources for society

- Society gains more organizations that are effective

There is a variety of methods for improving job enrichment (Hackman and Oldham, 1975):

- Skill Variety: Perform different tasks that require different skill. This differs from job enlargement that might require the employee to perform more tasks, but require the same set of skills.

- Task Identity: Create or perform a complete piece of work. This gives a sense of completion and responsibility for the product.

- Task Significant: This is the amount of impact that the work has on other people as the employee perceives.

- Autonomy: This gives employees discretion and control over job related decisions.

- Feedback: Information that tells workers how well they are performing. It can come directly from the job (task feedback) or verbally form someone else.

For a survey activity, see Hackman and Oldham's Five Dimensions of Motivating Potential.

Action Learning

An unheralded British academic was invited to try out his theories in Belgium—it led to an upturn in the Belgian economy. “Unless your ideas are ridiculed by experts they are worth nothing,” says the British academic Reg Revans, creator of action learning.

Action Learning can be viewed as a formula: [L = P + Q]:

- Learning (L) occurs through a combination of

- programmed knowledge (P) and

- the ability to ask insightful questions (Q).

Action learning has been widely used in Europe for combining formal management training with learning from experience. A typical program is conducted over a period of 6 to 9 months. Teams of learners with diverse backgrounds conduct field projects on complex organizational problems that require the use of skills learned in formal training sessions. The learning teams then meet periodically with a skilled instructor to discuss, analyze, and learn from their experiences.

Revans bases his learning method on a theory called System Beta, in that the learning process should closely approximate the scientific method. The model is cyclical—you proceed through the steps and when you reach the last step you relate the analysis to the original hypothesis and if need be, start the process again. The six steps are:

- Formulate Hypothesis (an idea or concept)

- Design Experiment (consider ways of testing truth or validity of idea or concept)

- Apply in Practice (put into effect, test for validity or truth)

- Observe Results (collect and process data on outcomes of test)

- Analyze Results (make sense of data)

- Compare Analysis (relate analysis to original hypothesis)

Note that you do not always have to enter this process at the first step, but you do have to complete all the steps in the process.

Revans suggest that all human learning at the individual level occurs through this process. Note that it covers what Jim Stewart (1991) calls the levels of existence:

- We think — cognitive domain

- We feel — affective domain

- We do — action domain

All three levels are interconnected, i.e., what we think influences us and is influenced by what we do and feel.

Change

In its simplest form, discontinuity in the work place is change. - Knoster and Villa, 2000

Our prefrontal cortex is a fast and agile computational device that is able to hold multiple threads of logic at once so that we can perform fast calculations. However, it has its limits with working memory in that it can only hold a handful of concepts at once, similar to the RAM in a PC. In addition, it burns lots of high energy glucose (blood sugar), which is expensive for the body to produce. Thus, when given lots of information, such as when a change is required, it has a tendency to overload and being directly linked to the amygdala (the emotional center of the brain) that controls our fight-or-flight response, it can cause severe physical and psychological discomfort. (Koch, 2006)

Our prefrontal cortex is marvelous for insight when not overloaded. However, for normal everyday use, our brain prefers to run off its hard-drive—the basal ganglia, which has a much larger storage area and stores memories and our habits. In addition, it sips rather than gulps food (glucose).

When we do something familiar and predictable, our brain is mainly using the basal ganglia, which is quite comforting to us. When we use our prefrontal cortex, we are looking for fight, flight, or insight. Too much change produces fight or flight syndromes. As change agents, we want to produce insight into our learners so that they are able to apply their knowledge and skills not just in the classroom, but also on the job.

And the way to help people come to insight is to allow them to come to their own resolution. These moments of insight or resolutions are called epiphanies—sudden intuitive leap of understanding that are quite pleasurable to us and act as rewards. Thus, you have to resist the urge to fill in the entire picture of change; rather you need to leave enough gaps so that the learners are allowed to make connections of their own. Doing too much for the learners can be just as bad, if not worse, than not doing enough.

Doing all the thinking for learners takes their brains out of action, which means they will not invest the energy into making new connections.

Next Steps

Next chapter: Diversity

Learning Activities:

References

Cunningham, J.B., Eberle, T. (1990). A Guide to Job Enrichment and Redesign. Personnel, Feb 1, p.57.

Davis , K. (1967). Human relations at work: The dynamics of organizational behavior. 9th ed., New York: McGraw-Hill

Hackman, J.R., Oldham, G.R. (1975). Development of the Job Diagnostic Survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, pp.159-70. May be found in Work Redesign.

Knoster, T., Villa, R., Thousand, J. (2000). A framework for thinking about systems change. Restructuring for caring and effective education: Piecing the puzzle together. Villa, Thousand (eds), pp.93-128. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Koch, C. (2006). The New Science of Change. CIO Magazine, Sep 15, pp54-56. Also available on the web: http://www.cio.com/archive/091506/change.html

Newstrom, J. W., Davis, K. (1993). Organizational Behavior: Human Behavior at Work. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Revans, R. W. (1982). The Origin and Growth of Action Learning. Hunt, England: Chatwell-Bratt, Bickley.

Schein, E. (1968). Organizational Socialization and the Profession of Management. Industrial Management Review. Vol.9, pp1-15.

Stewart, J. (1991). Managing Change Through Training and Development. London: Kogan Page.